A Jordanian midwife holds the first Syrian baby born in the Red Cross and Red Crescent hospital in the al Azraq camp in Jordan. Photo: IFRC

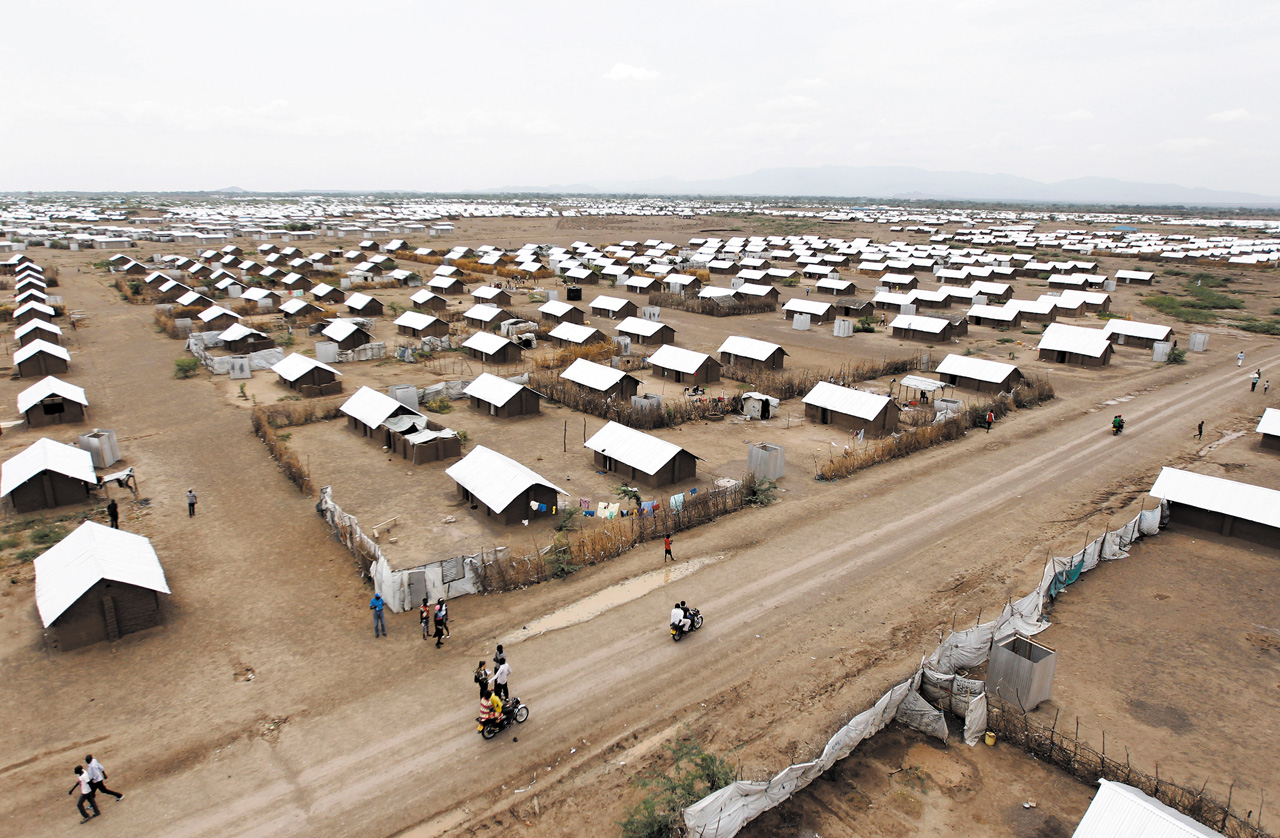

Now more than 25 years old, the Kakuma refugee camp, north-west of Kenya’s capital Nairobi, is the second largest in Kenya after the better-known complex of camps in Dadaab, near the border with Somalia. These recently constructed houses in Kakuma are an indication of the camp’s continued growth since its founding in 1991 as a safe haven for roughly 12,000 unaccompanied minors and others fleeing violence in Sudan. Photo: REUTERS/Thomas Mukoya

Established five years ago for Syrians fleeing civil war, the al Zaatari refugee camp in northern Jordan has quickly grown from 15,000 inhabitants to more than 80,000 people. Already, the camp shows signs of permanent settlement as residents make the best of their desperate situation. There are markets for clothes, electronics and food; coffee shops where men smoke sheesha pipes, even football tournaments. Here, Syrian children watch the final match in a camp tournament that coincided with the 2014 World Cup. Photo: REUTERS/Muhammad Hamed

Education is one of the greatest challenges facing refugees around the world and aid groups are struggling to meet the need. Here, Syrian refugee children sit in a UNICEF-supported classroom at a remedial education centre in the al Azraq refugee camp in Jordan. Photo: REUTERS/Muhammad Hamed

The al Azraq camp, east of Jordan’s capital, Amman, was built in 2013 as the population of Jordan’s al Zaatari camp grew beyond capacity. Below, a Syrian woman shops in one of the camp’s grocery stores after receiving humanitarian shopping vouchers. Photo: REUTERS/Muhammad Hamed

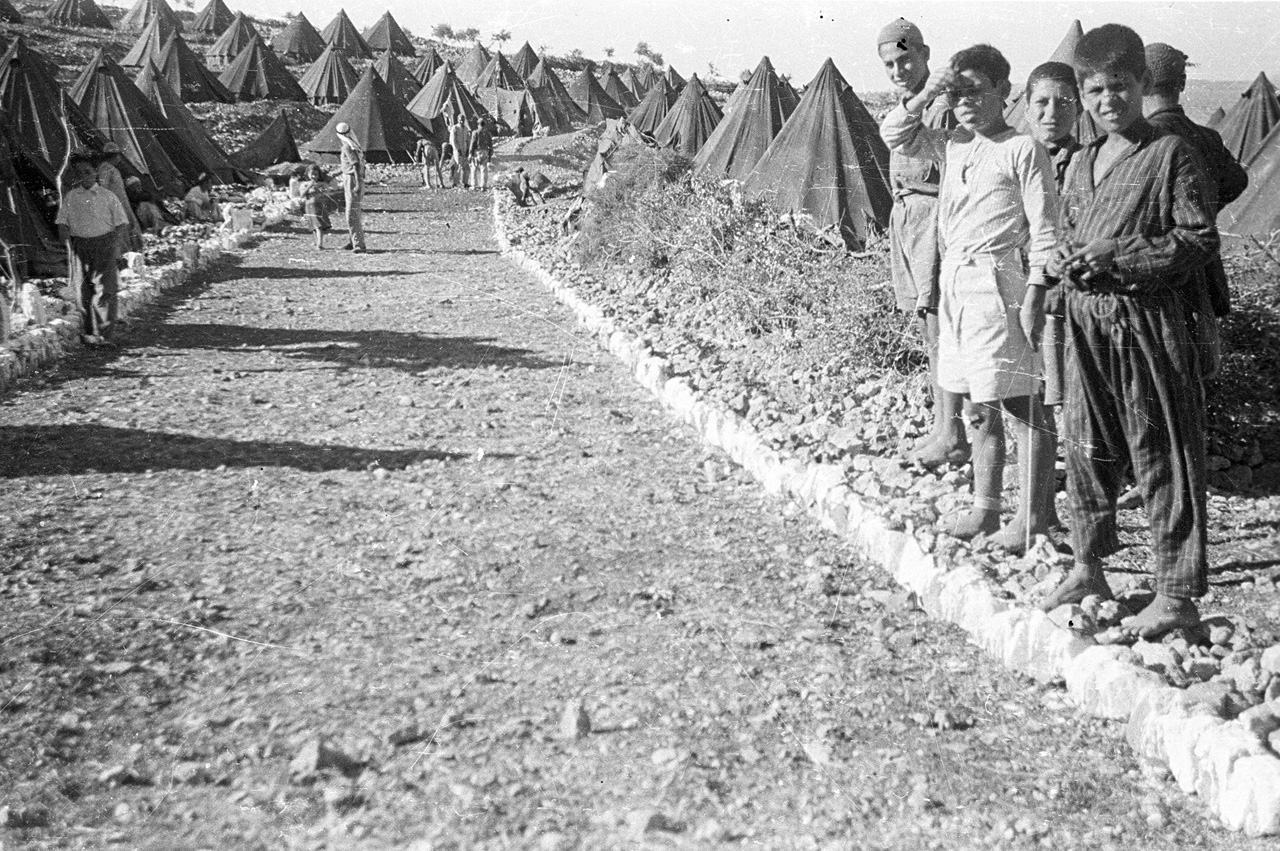

A 1948 photo from the ICRC archives shows the Jelazone camp, located in the West Bank, roughly 20 kilometres north of Jerusalem. Now, almost seven decades later, it looks and functions like a small town of some 15,000 inhabitants. Photo: ICRC

Though usually referred to as ‘camps’, many of the world’s oldest refugee settlements look, at least from the outside, more like city neighbourhoods. The Deheishe refugee camp in the West Bank town of Bethlehem is one example. Three generations of Palestinians have grown up in this camp, established after the 1948 Arab–Israeli war. Photo: REUTERS/Ammar Awad

While many people have heard of the Dadaab camp in Kenya, or Yarmouk in the suburbs of Damascus, Syria, some of the world’s oldest camps are less well known. The Mae La refugee camp in Thailand, for example, is one of the oldest refugee settlements in the world. Established more than 30 years ago, Mae La is home to some 50,000 people, most of whom fled violence and persecution in neighbouring Myanmar during the 1980s and 1990s. Photo: REUTERS/Chaiwat Subprasom

As new waves of violence cause displacement — both within countries and across borders — new camps are formed almost every month. Will these new camps be temporary or will residents end up spending their entire lives in these makeshift environments? Will the young girl pictured here live out her days away from the neighbourhood where she was born? The girl and her parents live at M’Poko camp, set up at the airport in Bangui, the capital of Central African Republic, after violence and civil strife rocked the country in 2013. Photo: Virginie Nguyen Hoang/ICR

After election-related violence in 2015 in Burundi forced more than 300,000 people to flee to neighbouring countries, long-established camps such as the already overcrowded, 20-year-old Nyarugusu camp in Tanzania were pushed to breaking point. Newly arriving refugees, such as the family pictured here, were brought to the recently reopened Mtendeli refugee camp, where the Tanzania Red Cross National Society operates a hospital and offers a range of health services. Photo: Niki Clark/American Red Cross

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Tech & Innovation

Tech & Innovation Climate Change

Climate Change Volunteers

Volunteers Health

Health Migration

Migration