The dilemma: a background on interference

The government ultimately agreed. But the real test was still to come. To fully appreciate the dilemma Bugnion and Beaumont would soon face, it’s important to understand Cambodia’s reticence towards foreign intervention. After the fall of the Khmer Rouge, the country had finally emerged from a long period throughout which outside forces — from Asia and beyond — had meddled with or controlled the country’s affairs.

In the decades following Cambodia’s independence from France in 1953, Prince Norodom Sihanouk, who led the country from 1960 to 1970, sought to remain neutral in the Cold War proxy conflict that was tearing apart its neighbour Viet Nam.

But not everyone agreed with Sihanouk’s neutrality given that the war going on in neighbouring Viet Nam was already spilling over Cambodia’s border. In 1970, Sihanouk was ousted and a new regime sought to stop North Viet Nam’s use of Cambodia as a means to transport supplies.

But because the new regime lacked credibility with the Cambodian population, the country quickly descended into civil war. The Khmer Rouge profited, taking control of nearly all Cambodia’s countryside.

“During this civil war, the ICRC was present in Cambodia with large relief and medical programmes, as well as family reunification services and other activities,” Bugnion recalls. “The ICRC and UNICEF were the only two organizations that stayed until the Khmer Rouge took Phnom Penh on 17 April 1975.

“On that day, the capital, which had a population of 2 million people, was completely emptied. There were no exceptions, neither for those injured in the war, nor the elderly, nor young women who had just given birth the night before.”

Without functioning institutions, a monetary system and no viable economy, people had to fend for themselves. Many were executed or sent to work camps. Some 2 million people were killed — roughly 25 per cent of the country’s then population of 8 million. “During that period, there was no possibility for the ICRC to act [within Cambodia],” Bugnion recalls.

A dilemma for Impartiality

Four years later, weakened by internal divisions, the Khmer Rouge fell to the Vietnamese forces, and the People’s Republic of Kampuchea was established. Six months after that, Beaumont and Bugnion were on the plane to Phnom Penh.

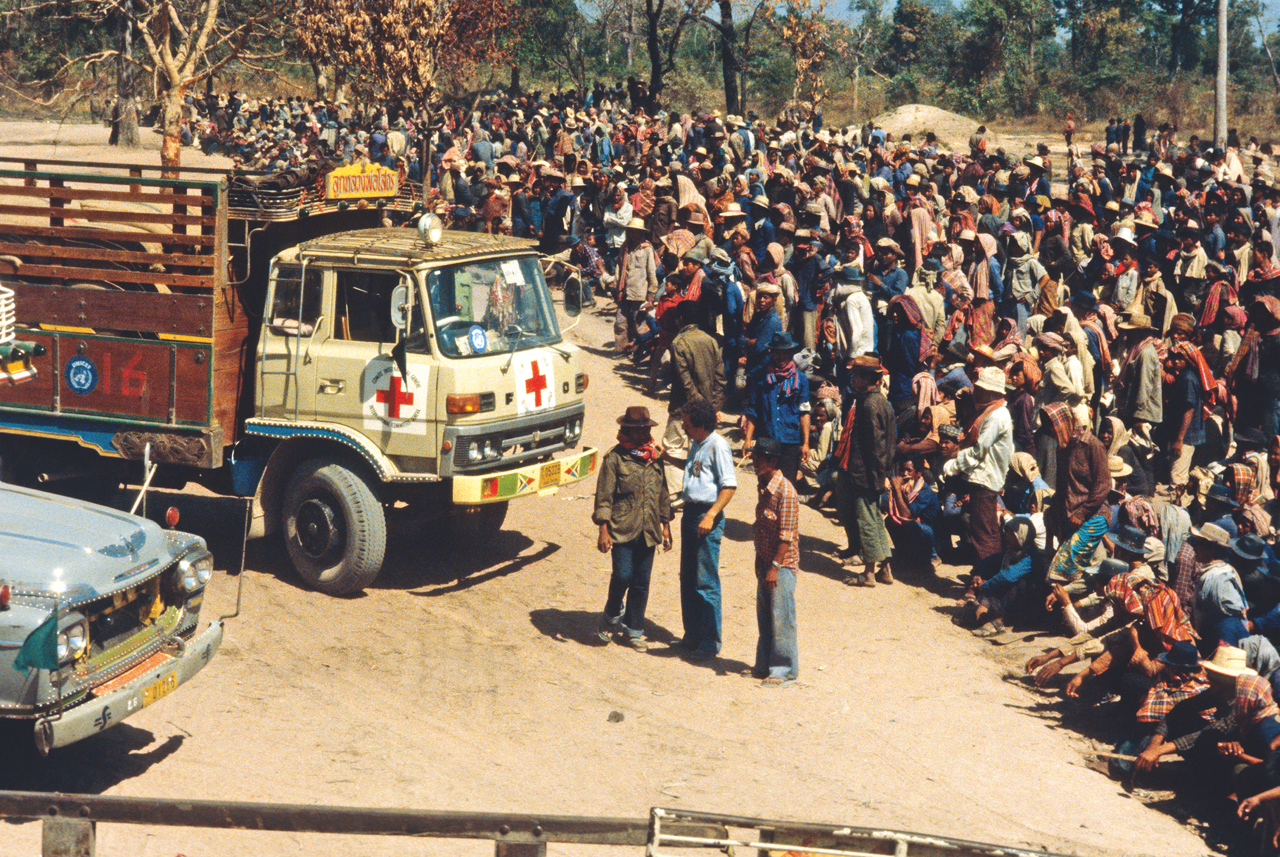

But just as the two were negotiating a relief package with new Cambodian authorities, another situation was developing near the Thai border. Seeking to escape the fighting, a massive exodus of refugees had been moving towards Thailand. At first, Thailand accepted the refugees. But as the numbers grew, it closed the border, leaving thousands trapped in border zones inside Cambodia controlled by the Khmer Rouge.

In response, the ICRC and UNICEF mounted a major relief action in favour of the trapped refugees. As neither organization could gain access to those refugees from the Cambodian side, they brought in supplies through Thailand.

“When the government of the People’s Republic of Kampuchea learned of this, it reacted in an extremely strong fashion,” Bugnion recalls. “To a certain extent, it was understandable. This was the reaction of a government that was not recognized by the international community and which had the feeling that these two humanitarian organizations were, in a sense, tramping their sovereignty.

“The government took a very firm position, saying, ‘If you want to engage and collaborate with us, it must be only with us and you must stop all your operations across the border’,” recalls Bugnion. It was not an idle threat: the authorities demanded their passports, granting them 48 more hours inside the country.

“It was extremely troubling because on the one hand we thought: it’s only by working with the government that we will be able to assist the majority of people living in Cambodia. But who are we to effectively ignore the situation of several tens of thousands of people, who are in an even worse situation?”

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Tech & Innovation

Tech & Innovation Climate Change

Climate Change Volunteers

Volunteers Health

Health Migration

Migration