In the jargon of humanitarian organizations, a “displaced person” is someone forced to flee from one part of their country to another.

But this legalistic terminology obscures the horrifying realities these people face in a country torn apart by conflict. In Yemen, about 4 million have lost their property and their homes over the past seven years, forced to find safer areas in an effort to simply survive.

One of them is Souad. Along with her four children and her late husband, Souad left her village in Rayma for the capital Sana’a and then to a camp for “displaced persons” in Ma’rib.

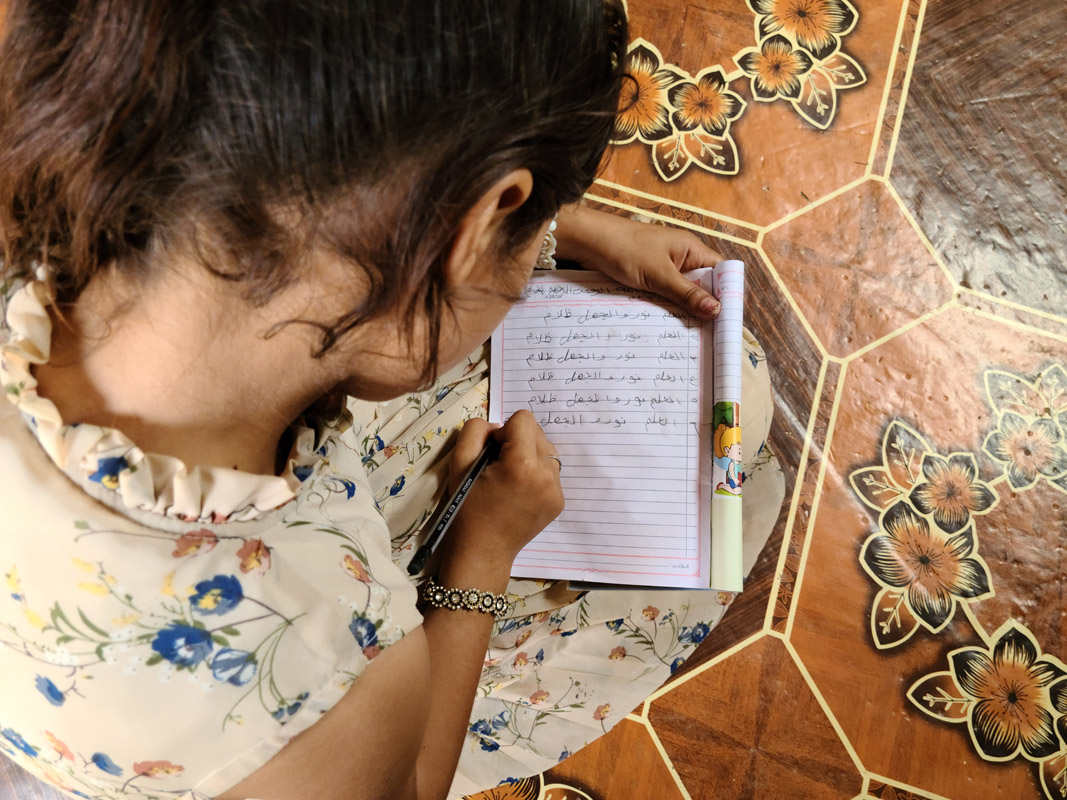

“The war forced us to leave our home and go into displacement camps, where we had to confront our pain and suffering alone,” says Souad, whose story reveals another important reality: Even people facing tremendous hardship cannot be simply defined by labels or categories such as “displaced person” or “war victim”.

Indeed the case of Souad shows us, even people who live in camps for the displaced are so much more. As Souad tells her story inside her small dwelling on a recent afternoon, words such as mother, father, volunteer, teacher, scholar and survivor come to mind.

“As the war continued and worsened, many others, like me, chose to leave their homes and go to governorates they don’t know. In an attempt to avoid the scourge of war we found ourselves stuck — forced to move between the various regions of Yemen. We are now settled in the Al-Jafinah camp, living in poor conditions.”

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Tech & Innovation

Tech & Innovation Climate Change

Climate Change Volunteers

Volunteers Health

Health Migration

Migration