“If we can better unite ourselves for the common cause, perhaps we can present ourselves more strongly to the outside world,” says Konoé, sitting aboard the Tashkent-bound train. “By uniting our power of humanity, we can do much more. Then we need to improve the capacity of each National Society, otherwise, as a Movement, we cannot exert our power and address challenges.”

These trips are also a chance to maintain a connection to the grass-roots side of the organization, says Konoé, who has been president of the Japanese Red Cross Society since 2005. “You have to see with your own eyes and listen with your own ears to assess the reality on the ground. Feeling empathy is also important. As a basic policy, whenever a major disaster hits, I try to make a visit.”

Shortly after taking office, Konoé visited his first disaster zone as IFRC president after a 7.0 magnitude earthquake struck the Caribbean island of Haiti in January 2010. A few months later, Pakistan experienced its worst flooding in recorded history, with up to 20 million people affected. Other catastrophes followed, including a devastating earthquake and tsunami in Konoé’s home country in 2011, as well as numerous conflicts and refugee crises.

Konoé, 78, is no stranger to such scenes of calamity and suffering. He has spent more than five decades with the Movement and during that time, has been involved in some 30 relief missions around the world. One early, formative experience was a three-month stint with a Japanese Red Cross Society medical team in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) in 1970, following the deadliest tropical cyclone on record.

“That was a typically complex emergency, and similar situations exist in many parts of the world today,” says the tall, slender Konoé, sitting in his office in Tokyo one midweek morning. “So we can still use the lessons we learned from that time. The problems are the same today, but the international community is better equipped and organized, though investment in preparedness is still not enough.”

Humanity’s ‘lifeblood’

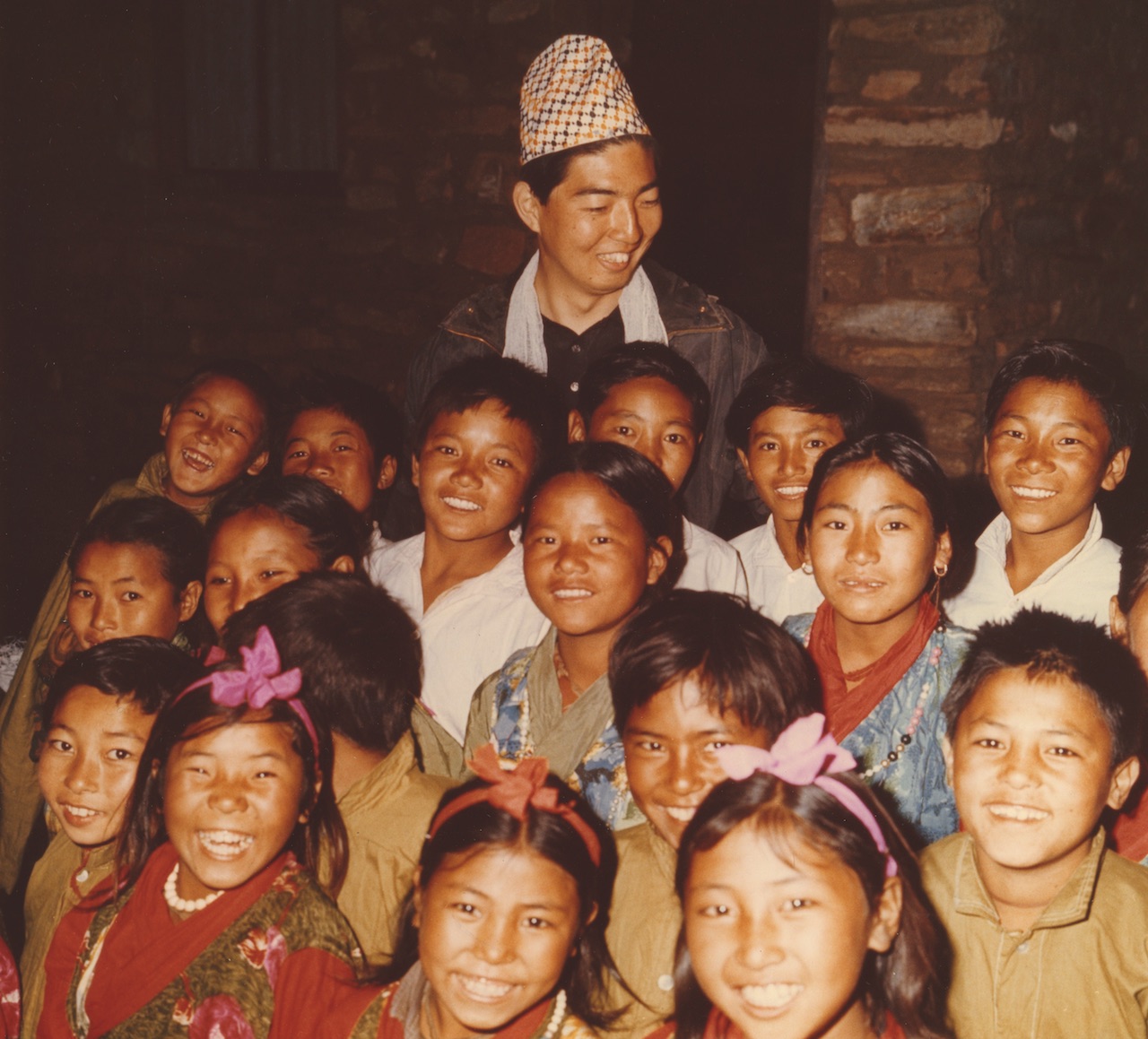

Visiting with volunteers — who Konoé describes as the ‘lifeblood’ of the humanitarian network — is always a highlight of his missions. Fostering volunteerism has been a priority during his tenure. A volunteer charter, which aims to recognize, protect and encourage volunteers while clarifying their rights and responsibilities, is expected to be adopted at the upcoming General Assembly.

Strong volunteer networks also require strong National Societies. But the IFRC needs to acknowledge weaknesses within its network and find solutions. One of those weak points is that many National Societies are still far too dependent on a narrow source of income, often funding provided by a limited number of sister National Societies.

And while a major disaster may draw the media spotlight and an influx of donations to a National Society, Konoé argues that once world attention has moved on, National Societies need to find innovative ways to fund-raise for long-term recovery efforts and for less visible but vital medical and social welfare programmes.

Recalling the massive relief operation during the Ethiopian famine of the 1980s, Konoé explains how the IFRC and National Societies worked together to address some of the root causes of the large-scale hunger.

“I like that kind of multifaceted approach involving many actors,” he says. “Some argue that it’s not the work of the Red Cross and Red Crescent, that it’s too ambitious. That may be true, but without multidisciplinary approaches to solving this kind of problem, nothing will improve.”

The One Billion Coalition for Resilience — which brings people, businesses, communities, organizations and government together to reduce risks and improve health and safety — is one example of multi-sector collaboration that Konoé has enthusiastically supported.

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Tech & Innovation

Tech & Innovation Climate Change

Climate Change Volunteers

Volunteers Health

Health Migration

Migration