In the town of Musina, along South Africa’s northern border with Zimbabwe, Marrieth Ndlela talks to a young man who travelled more than 1,000 kilometers — by foot, car and bus — from the Democratic Republic of the Congo [DRC] looking for a safe haven.

“I remember the first month I arrived here, I was afraid,” says Amman, who was a music teacher when he fled his country due to instability and violence. “When you arrive in a new country and you don’t know anyone, it’s scary. I was afraid about the life here… especially in Pretoria, the thieves, you know, can kill you anytime. And I’ve seen it. They killed some guy in front of me. I was really afraid.”

Sadly, it is not uncommon for migrants, including asylum seekers and refugees, to experience such shocks and perils along their journeys. Many did not want to leave home but were forced away by armed violence. Others travelled through areas rife with banditry, were stopped or arrested by police or have stayed in communities where not everyone made them feel welcome.

Here in Musina, migrants come from as far away as Ethiopia and Eritrea, DRC and Tanzania, as well as neighboring countries such as Zambia and Mozambique. Given all this, volunteers in Musina know migrants often have very good reason to be wary of anyone who might approach them.

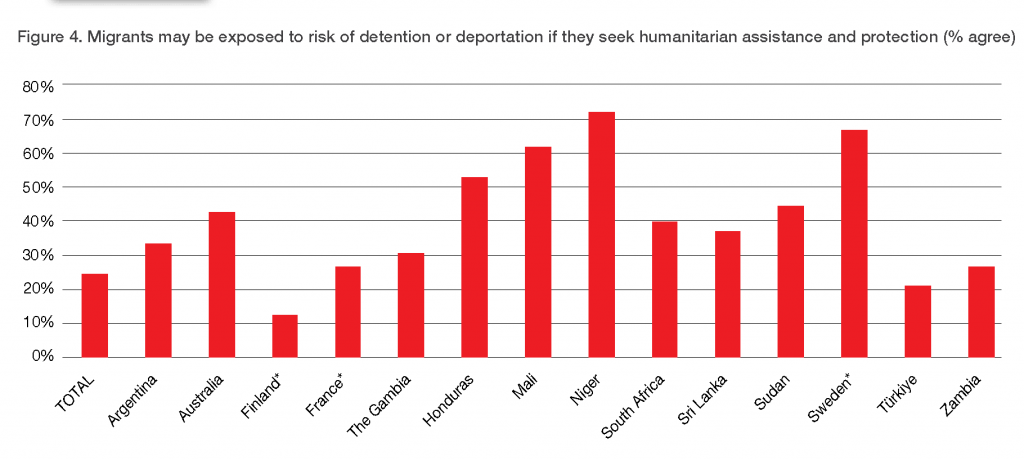

This distrust can dramatically increase their vulnerability if they are afraid to seek help or protection, says Ndela, who volunteers for the local Musina branch of the South African Red Cross Society as part of teams that offer tests for infectious diseases, as well as services that help migrants stay in touch with family members far away.

“Trust is very important between volunteers and migrants,” says Ndela. “So what we do as volunteers is to build a relationship with migrants. We go daily to places where migrants feel safe so that they get to be used to us and get to know who we are.”

What are migrants most distrustful about? “They are worried what might happen to them,” Ndela says, “because maybe they don’t have documents or worry that their documents are invalid. Most of them are worried of being deported to their country of origin. So we tell them that we do not share any information they give us, and that we help everyone whether they are documented or not.”

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Red Cross Red Crescent magazine

Tech & Innovation

Tech & Innovation Climate Change

Climate Change Volunteers

Volunteers Health

Health